Last week I was honored to attend the commissioning ceremony of a dear friend who is launching into a new season of ministry. When you are already a skilled preacher, exegete, and writer with years of experience, why get commissioned now? Because a “sending” kind of ceremony acts as a mile-marker, a moment to reflect on calling and direction and to acknowledge God’s anointing for future service to his kingdom.

My favorite moment? The prayer. Sitting on a throne-like chair, she bowed her head as her friend and mentor laid a hand on her head and read an ancient prayer over her.

Holy and lofty God, who sees humble women, who has chosen both the infirm and the powerful, O honored one, impart, a spirit of power upon this your servant, and in your truth strengthen her so that, fulfilling your commandment and laboring in your sanctuary, she may be for you an honored vessel and may give glory on the day, O Lord, on which you will glorify your humble ones.

Grant her the power of happily practicing the teachings prescribed by you. Grant her, O Lord, a spirit of humility, of (the Spirit’s) power and patience and kindness, so that she might, bearing your burden with ineffable joy, sustain her labors.

Truly, Lord God, who knows our infirmity, perfect your servant for the glory of your house; strengthen her for edification and as a shining example. God, sanctify her, make her wise and comfort her, because, God our Father, your kingdom is blessed and glorious.

(In the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Amen.)1

This prayer was once said at the appointment ceremonies for the ecclesial office of widows.

Church Fathers … and Mothers

Does it surprise you to learn that women were so integral to church life and leadership in the 300–400s that they held official positions of deacon, widow, and virgin? The documents I quote here show that practices within the early church varied widely among faith communities across the south, east, and west. The Coptic Church in Ethiopia structured their leadership somewhat differently from the Syrian church, which had different customs and rules from the Roman Church. While theology remained mostly aligned, church practices were locally driven (much like politics), giving rise to positions for women in some churches but not others, as far as we know. It took centuries beyond the Nicene era for traditions to become institutionalized across the regions.

In a previous post I explored the existence and history of female deacons. More on them next time, and in part three we will discuss the official position and status of virgins. But now, on to the leading ladies of the early church.

What Makes One a Widow?

The prayer above is titled “Prayer of the Institution of Widows Who Sit in Front.” Widows were more than once-married women whose husbands had died. They were usually elder women who dedicated themselves to serving the church through prayer, fasting, service, and mentoring younger women. They could have been never-married women or those whose husbands had died—both would be called widow if included in the office.

What do we mean by “office” of the church? In her paper to the 2021 Evangelical Theological Society annual meeting, scholar Sandra Glahn noted,

The word office does not appear in the New Testament, so what does office mean? . . . office refers to a position of service in the church that carries with it prerequisites or qualifications of Christian experience and character or maturity. Unlike spiritual gifts, bestowed by the Holy Spirit on all believers, offices require vetting, and humans are involved in deciding who will hold them.

Qualifications of a Widow

An early manual directing church leaders on proper ecclesial structure clarified that the office of widow was not ordination2 as a priest experienced:

A widow is not ordained; yet if she has lost her husband a great while, and has lived soberly and unblameably, and has taken extraordinary care of her family, as Judith and Anna — those women of great reputation— let her be chosen into the order of widows. But if she has lately lost her yokefellow, let her not be believed, but let her youth be judged of by the time; for the affections do sometimes grow aged with men, if they be not restrained by a better bridle.

What Did Widows Do?

The prophetess Anna, whom we meet in Luke 2, is a prototype of the widows who would later become a clerical order. Their duties “included prayer, fasting, visiting and laying hands on the sick, making clothes, and doing good works.” Widows were sometimes called presbytera, the female form of presbyter (1 Tim 5:2), recognized alongside male leaders such as bishops, presbyters (priests/elders), and deacons.

After appointing a woman into the order of widows, church leaders gave directions for their ministry:

Let them enjoy solitary time to pray and fast. But also … when a widow “gives thanks or praise, if she have friends’ like-minded virgins, it is well that they pray with her for the sake of the Amen.”

Here we see commendation for a ministry primarily devoted to prayer and praise. But the widow’s “job” includes joining with other women as well. The early church leaders expressed concern for widows’ good reputations, per 1 Timothy 5:9–10.

New Testament scholar and early church backgrounds expert Dr. Lynn Cohick writes, “Many ancient commentators suggest that the woman is called not only to bear children but to raise them in the Christian faith. And with the rise of asceticism, the text was interpreted metaphorically as well to include those women who took vows of celibacy or who were widows. The emphasis was on "birthing" virtues of holiness, not raising a family. The childless woman's good works substituted for children.”

As the institutionalization of the church increased, “. . . the office of widow dwindled by the middle of the third century with the rise of virginity as the ideal and the rise of the deaconess,” said Glahn, citing historical sources. But epigraphical evidence shows the scattered proof, across the lands of the Roman Empire, of women who held ecclesiastical office.

Where are the mothers in your church?

What Does the Office of Widows Mean for the Church Now?

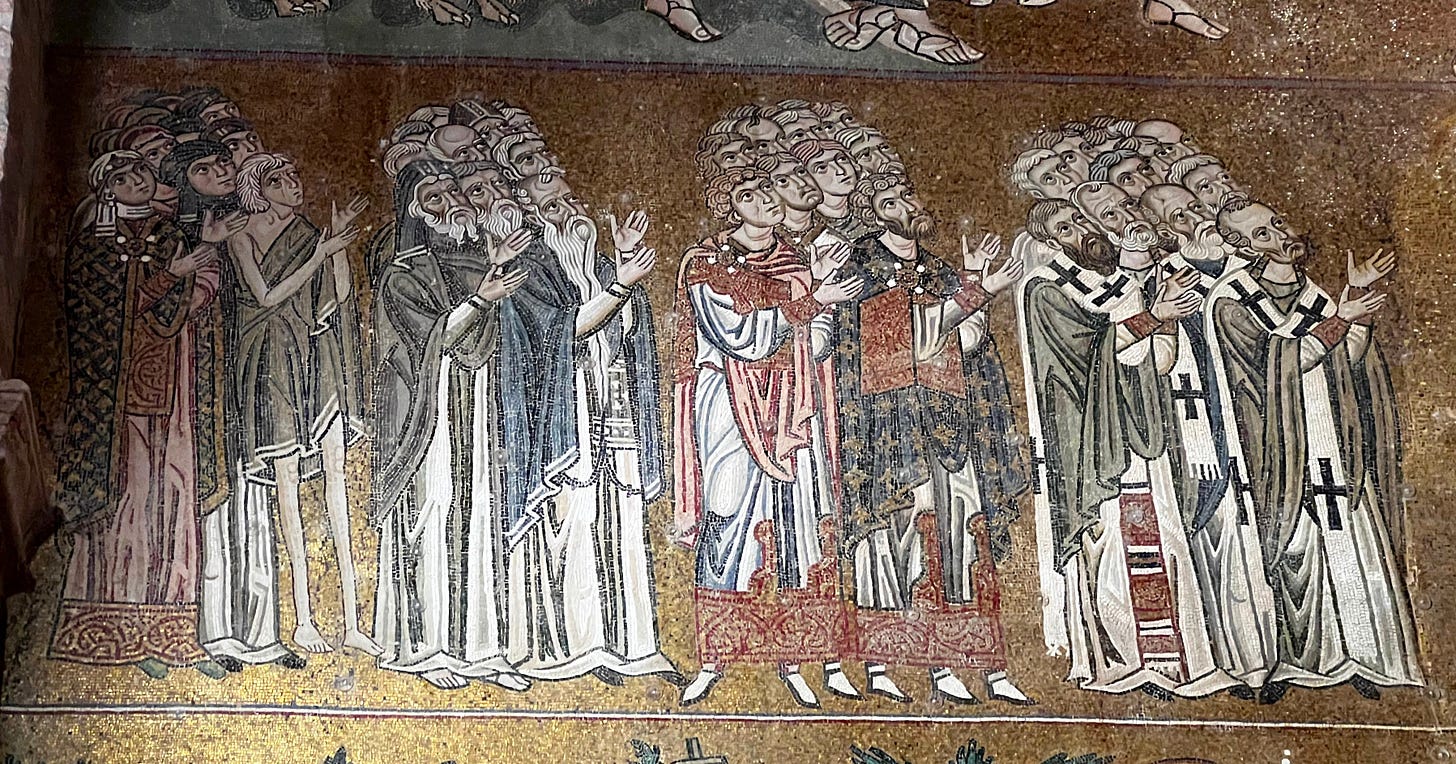

Over the centuries, some women rose to high ranks within the church. They wore the symbols of a bishop (see the image of Mary at the top)3, established and ruled monasteries and convents, and were recognized as spiritual shepherds of their communities.

Images such as the reliquary below show that, during communion, women stood at the altar, adjacent to the bishops, presbyters, and deacons. From the beginning, it seems, women who fit the qualifications of 1 Timothy 5 were invited to serve the church in official capacities. They participated in leading core worship responsibilities. The family motif so prevalent in Paul’s letters was evident—fathers and mothers, sisters and brothers, all serving together to encourage one another toward Christlike love and good deeds.

What are we doing in our churches today to resemble a robust family of God? Where are the mothers of your church? Do you know them? Are they vetted, visible, active, and authorized? When worship, preaching, ushering, greeting, helping, and serving communion are dominated by men, often fully excluding women, that church is unbalanced (something children and visitors notice!).

Scripture and history tell us that women in church leadership are not a product of second-wave feminism. They are not “giving into culture.” Scripture reveals God’s desire for a diversity of church leadership, based on the Spirit’s gifting and the leaders’ character—a practice that generations of believers adopted.

Like my friend, women who seek to serve the church today with their gifts of leadership, administration, teaching, prophecy, etc. are obeying the Spirit who gave them those gifts. In what ways can you recognize and commission them to join their brothers in honored service?

From the Testamentum Domini 1.41., a church order (how to do church) composed originally in Greek which survives today in Syriac, Ethiopic, and Arabic (with possible fragments in Greek and Coptic) as books one and two of the canonical collection known as the Clementine Octateuch.

Nor can we equate today’s ordinations with those of the early church, for the understanding of ordination changed somewhere in the twelfth to thirteenth centuries. Comparing them now would be an apples-to-oranges scenario.

The mosaic today shows a simple red line on Mary’s pallium, but an 1899 painting of the scene clearly portrays a red cross. Sometime in the first decade of the 1900s, the red horizontal tiles were replaced with white, obscuring the symbol of leadership on a woman. Scholars suggest the defacing was intentional.

So fascinating! Makes me want to read more Church history and get a fuller picture than I currently have. Any indication if women (Widows or otherwise) preached in the mixed congregation?