Today, June 2, the church universal celebrates the life and death of Blandina, a second-century slave who was martyred for her faith. But before we look closely at what we know about her, I want to explore (briefly) the kind of character it took to submit to the horrors of the arena.

Roman (Male) Virtues

Leading church fathers tended to divide character virtues according to sex—certain virtues looked one way when expressed by men but were embodied differently by women. Some virtues were considered male-only, so if women somehow exhibited that virtue, they were said to become men. Courage was one such “male” virtue, one of the most valued characteristics of the honorable Roman man.

Fourth-century church scholars such as Ambrose, Jerome, and Augustine were heavily influenced by the Roman philosophers, who taught that women were innately flawed humans. The male body and mind was normative, in their view, and women’s were deficient. When these church fathers told stories about believers from the first—third centuries, they struggled with how to portray the women martyrs.

Ambrose described people relative to their faith, or lack of faith, in Christ: “One who does not believe is a woman and should be designated in the name of that sex, whereas one who believes progresses to perfect manhood.”1

Augustine (4th c), in his sermons on Perpetua and Felicity, two women martyred in 202, described them: “What, after all, could be more glorious than these women, whom men can more easily admire than imitate? … according to the inner self they are found to be neither male nor female; so that even as regards the femininity of the body, the sex of the flesh is concealed by the virtue of the mind, and one is reluctant to think about a condition in their members that never showed in their deeds.”2 (i.e., They acted like men in their deaths even though during their lives they were obviously women. Gus was quite the misogynist.)

Jerome: “. . . when [a woman] wishes to serve Christ more than the world, then she will cease to be a woman, and will be called man.”3

To the fourth-century scholars, men and women were made of different stuff both physically and spiritually. So when women were seen taking on the characteristics typically ascribed to men, they had no category for such women. Even Perpetua herself, dreaming of her forthcoming stance in the arena, described herself as becoming a man—meaning, she would stand tall with courage, face the beasts, and declare her faith boldly without recanting.

The Slave Woman Blandina

Some twenty-five years before Perpetua died in the arena, a female slave and her mistress—both Christians—were taken before the Roman governor in Lyons, in what is now southern France.4

. . . in 177 . . . Many of the principal Christians were brought before the Roman governor. Among them was a slave, Blandina; and her mistress, also a Christian. . .

“While Blandina’s mistress is portrayed as a hand-wringing wreck,” (Cohick and Hughes, p 96) the slave demonstrated astonishing strength under duress.

Blandina was filled with such power that she was released and rescued from those who took turns in torturing her in every way from morning until evening, and they themselves confessed that they were beaten . . . But the blessed woman, like a noble athlete, kept gaining in vigour in her confession, and found comfort and rest and freedom from pain from what was done to her by saying, “I am a Christian woman and nothing wicked happens among us.”

Not only did Blandina display “masculine” courage and strength, she revealed a rock-solid faith inextricably linked with her sex: “I am a Christian woman.” Though she be little, and weak, and defenseless, and female … she is, in Christ, mighty and strong and victorious. Eusebius offers more details of her suffering:

But the blessed Blandina, last of all, like a noble mother who had encouraged her children and sent them forth triumphant to the king, having herself endured all the tortures of the children, hastened to them, rejoicing and glad at her departure as though invited to a marriage feast rather than cast to the beasts. . . the heathen themselves confessed that never before among them had a woman suffered so much and so long.

The pagans in 177 took her identity as a woman into account when they recalled her fortitude. She endured a variety of tortures along with her brothers in the faith who had accompanied her into the arena, even though physically she was disadvantaged compared to them. But her courage and strength inspired them even in their own last moments:

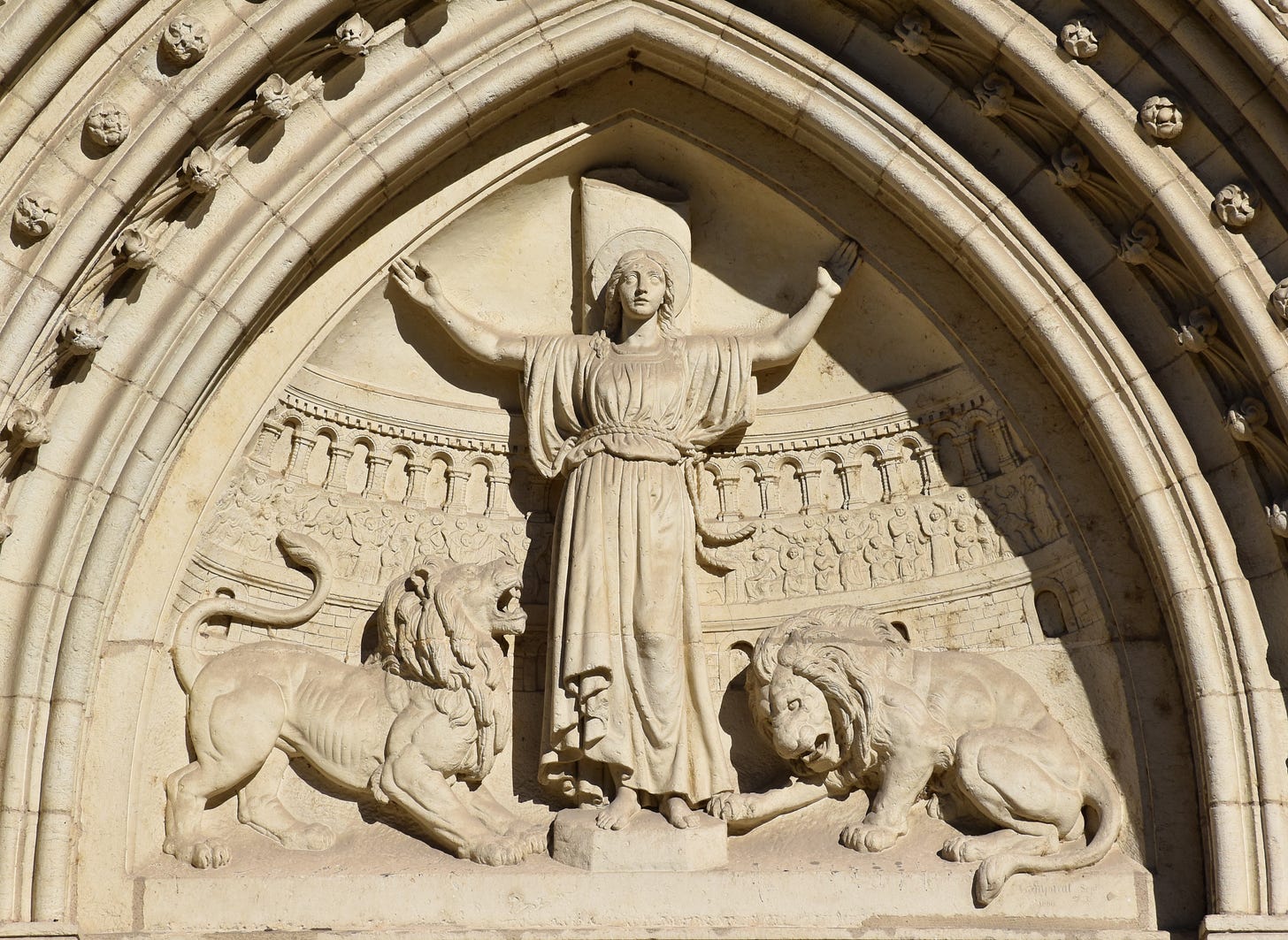

Blandina was hung on a stake and offered as a prey to the wild beasts that were let in. She seemed to be hanging in the shape of a cross, and by her continuous prayer gave great zeal to the combatants, while they looked on during the contest, and with their outward eyes saw in the form of their sister him who was crucified for them, to persuade those who believe on him that all who suffer for the glory of Christ have forever fellowship with the living God.

Blandina’s final suffering, hung on a stake as if on a cross, became a picture of Jesus himself to her fellow sufferers in the arena. In her, they saw their savior and were inspired to stand firm to the end, to trust that their suffering would end in glory.

Shattering Cultural Norms

Imaging Christ

Blandina’s fellow martyrs saw her as a picture of Christ. They didn’t limit themselves to the Roman idea of certain virtues belonging to men and others to women. Her faith witnessed to the reality of Paul’s words to the Galatians: “For those of you who were baptized into Christ have been clothed with Christ. There is no Jew or Greek, slave or free, male and female; since you are all one in Christ Jesus” (3:27–28). A woman was just as qualified as a man—indeed, the person’s sex played no role at all—in imaging Christ to the world. What mattered was her faith and obedience.

Reasserting Humanity

Blandina was in the arena with her mistress, a fellow believer, and a group of mostly or all men she counted as brothers in Christ. That the story told of those days centers on the female slave demonstrates the power of the gospel to subvert cultural norms. First a woman, then a slave—gender bias and class distinctions mattered nothing. Eusebius described her behavior in maternal terms: “like a noble mother who had encouraged her children and sent them forth triumphant to the king. . .”

Cohick and Hughes comment:

“The recounting of her tortured body resisting death, so as to die on her own terms, serves as a purposeful parallel to Jesus’s approach to his own death. The author of the letter interprets her endurance through trials as mounting proof of her defeat of the devil and encouragement for fellow Christians… Blandina's mothering in the arena subverts the destruction of status and humanity associated with the arena.” (Christian Women in the Patristic World, 97–98)

Inspiration from Blandina

Christlikeness knows no gender.

Each of us is meant to demonstrate our faith in our current contexts. We ought not let cultural distinctions and limitations affect our response to God’s call. Let’s broaden our net beyond our cultural moment while narrowing our perspective to that of Scripture. Have you been pigeonholed into an “acceptable” kind of service? Do you limit yourself based on unscriptural criteria? Or are you in a position of influence and find yourself (wrongly) including gender or class in a person’s suitability? Blandina has shown us what Christ can do through each of us when we live in his strength. How do you image Christ today?

Encourage one another.

We aren’t in the arena, but we could be in the trenches at any moment. What can we do to buoy our fellow sufferers, to encourage the disappointed, to carry the weak? Consider a few very basic ideas:

Communicate—Write notes, send a text, make a call. Let people know you are thinking about them. Sit and talk face to face. And if you are actually praying for them, then you can tell them you are.

Listen—Be a safe person, a shoulder to cry on, an attentive ear, a pair of locked lips who will hold confidences tightly.

Share—Depending on our circumstances, we may give financially where needed. But we might also be generous with our information and connections, offering our influence on others’ behalf. Let’s circle around those in need and offer tangible helps in our own gifting and situations.

Be a Berean.

Just because the church fathers—or our favorite Bible preachers—say something, doesn’t make it true. For all their wisdom on the Incarnation, the Trinity, and other insights into God’s nature, many of the church fathers brought Roman ideas about gender into their theology. Ambrose, Jerome, and Augustine (named above), among others, believed inaccurate ideas about women that bled into their interpretation of Scripture and their applications in the life of the church. We must check all scholarship against the whole of Scripture, no matter what big names—past or present—are teaching.

“they received the word with eagerness and examined the Scriptures daily to see if these things were so.” Acts 17:11.

St. Ambrose, Expositionis in evangelius secundum Lucum libri X.161, in PL 15:1844.

Augustine, Sermon 280.

St. Jerome, Commentarius in Epistolam ad Ephesios III.5 in PL 26:567a.

Unless otherwise noted, the blocked material in this section comes from Ecclesiastical History 5.1.3–63, by Eusebius.

“Christlikeness knows no gender.” LETS GOOOOO!!!!🔥🔥